The Centipede Game presents a fascinating paradox in game theory. It’s a seemingly simple game of repeated choices, where two or more players sequentially decide whether to cooperate or defect, with payoffs increasing with each round of cooperation. However, the game’s structure, based on backward induction, often leads to outcomes that defy rational self-interest, revealing intriguing insights into human behavior and the limits of purely rational decision-making.

This exploration will delve into the mechanics of the Centipede Game, examining its rules, payoff structures, and the decision-making processes involved. We’ll analyze experimental evidence that demonstrates how real-world behavior often diverges from theoretical predictions, highlighting the influence of psychological factors like trust and risk aversion. Furthermore, we’ll explore variations of the game and its applications in diverse fields, from international relations to business negotiations.

Game Mechanics of the Centipede Game

The Centipede Game is a fascinating game in game theory known for its paradoxical results. It highlights the conflict between rational self-interest and cooperative behavior. Understanding its mechanics is crucial to grasping its implications.

Rules and Structure

The Centipede Game involves two or more players who take turns deciding whether to “cooperate” or “defect.” Each turn, the “pot” of money grows. If a player defects, they take the majority of the current pot, while the other player(s) receive a smaller amount (or nothing). If all players cooperate until the end, they share a larger pot. The game ends when a player defects or the pre-determined number of turns is reached.

Decision-Making Process

At each stage, players must weigh the immediate payoff of defecting against the potential for a larger payoff if all players continue to cooperate. The decision is influenced by the perceived rationality of other players and the risk aversion of the individual player. A player might cooperate, hoping others will too, leading to a greater final payoff. Alternatively, a player might defect, securing a guaranteed payoff, even if it’s smaller than the potential payoff from continued cooperation.

Payoff Structures and Their Impact

Different payoff structures significantly alter player behavior. A structure with a rapidly increasing pot incentivizes cooperation for more turns. Conversely, a structure with a slowly increasing pot or a large payoff for the first defector might lead to early defection. The relative value of the immediate gain versus the potential future gain shapes the strategic choices.

Visual Representation of a 4-Player Centipede Game

Below is a simplified representation of a 4-player Centipede Game. Note that this only shows a few possible paths, and the actual game tree is much larger. The numbers represent the payoffs for each player (Player 1, Player 2, Player 3, Player 4) in that order.

| Stage | Player 1 Choice | Player 2 Choice | Player 3 Choice | Player 4 Choice | Payoffs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cooperate | – | – | – | – |

| 2 | – | Cooperate | – | – | – |

| 3 | – | – | Cooperate | – | – |

| 4 | – | – | – | Cooperate | (4,4,4,4) |

| 4 | – | – | – | Defect | (3,3,3,5) |

| 3 | – | – | Defect | – | (2,2,6,0) |

| 2 | – | Defect | – | – | (1,7,0,0) |

| 1 | Defect | – | – | – | (8,0,0,0) |

Rationality and the Centipede Game

The Centipede Game poses a significant challenge to traditional game theory, particularly the concept of rationality.

Backward Induction

Backward induction, a key concept in game theory, suggests that rational players should work backward from the final stage of the game to determine their optimal strategy. In the Centipede Game, this reasoning leads to the prediction that the first player should defect immediately, as any cooperation is irrational given the potential for greater gain through defection.

Rational Self-Interest vs. Cooperative Behavior

The Centipede Game highlights the tension between rational self-interest (defecting early) and the potential for mutual gain through cooperation. While backward induction suggests immediate defection, experimental evidence consistently shows that players often cooperate for several rounds before defecting.

Predicted Outcome vs. Observed Behavior

Rational choice theory predicts that all rational players will defect at the first opportunity. However, experiments reveal that this prediction is often inaccurate. Players frequently cooperate, demonstrating that factors beyond pure rationality influence decision-making.

Altered Payoff Matrix and Outcome Change

A slight alteration to the payoff matrix can drastically change the game’s outcome. For instance, increasing the payoff for cooperation at each stage, while maintaining a significant advantage for the first defector, might encourage more cooperation. Conversely, making the payoff for early defection disproportionately high would likely lead to earlier defections.

Experimental Evidence and Behavioral Economics

Numerous experiments have explored human behavior in the Centipede Game, revealing interesting deviations from the predictions of rational choice theory.

The Centipede Game is a classic example of game theory, showing how rational choices can lead to suboptimal outcomes. Think about the strategic implications – it’s all about trust and anticipating your opponent’s moves. Understanding the nuances of power dynamics involved can be similar to understanding the subtle social signals conveyed by a dress coat meaning , which itself can signal status or intention.

Ultimately, in both the Centipede Game and social interactions, your understanding of context and your opponent’s likely actions is key to success.

Findings from Real-World Experiments

Experiments consistently show that players often cooperate for more turns than predicted by backward induction. The average number of turns before defection varies depending on the payoff structure and the number of players. The frequency of cooperation is higher than expected based on purely rational models.

Deviations from Rational Choice Theory

The common deviation is the persistent cooperation observed in many experiments. This suggests that factors such as trust, altruism, risk aversion, and social norms play a significant role in shaping player decisions. The belief that other players will also cooperate can lead to a cascade of cooperative behavior.

Experimental Results

| Player Count | Average Number of Turns | Frequency of Cooperation |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3-5 (varies greatly based on payoff structure) | High, but significantly less than 100% |

| 3 | Lower than 2-player games, often ending sooner | Lower than 2-player games |

| 4+ | Generally lower still, with earlier defection | Generally lower still |

Note: These are general trends; specific results vary widely depending on experimental design and participant demographics.

Psychological Factors, Centipede game

Psychological factors such as trust, reciprocity, fairness, and risk aversion significantly influence player decisions. Players may cooperate based on trust in others, a desire for reciprocity, a sense of fairness, or a reluctance to take risks.

Variations and Extensions of the Centipede Game

The basic Centipede Game can be modified in various ways to explore different aspects of strategic decision-making.

Modifications and Strategic Implications

Variations include changing the number of players, altering the payoff structure (e.g., making the payoff increase exponentially or adding penalties for defection), and introducing incomplete information. These changes significantly affect the strategic considerations and the likelihood of cooperation. Increasing the number of players generally leads to earlier defection, as the risk of another player defecting increases with more players.

Impact of Game Parameters on Cooperation

A steeper payoff increase incentivizes cooperation, while a flatter payoff structure encourages earlier defection. Introducing penalties for defection can also promote cooperation. The game’s parameters directly influence the balance between immediate gain and long-term potential.

Hypothetical Scenario with Modified Game

Imagine a 3-player Centipede Game where the payoff for cooperation doubles at each stage, but the first defector gets 10 times the current pot. The increased payoff for cooperation might lead to longer periods of cooperation, but the significantly higher reward for defection could still result in early defection, particularly by players who perceive a high likelihood of others defecting later.

Applications and Interpretations of the Centipede Game

The Centipede Game’s simple structure allows it to model various real-world scenarios.

Real-World Applications

The game can model situations like arms races (where escalation can lead to mutual destruction), environmental agreements (where cooperation is crucial but individual incentives to defect exist), and international relations (where trust and cooperation are essential for stability).

Implications for Understanding Social Phenomena

The Centipede Game illustrates concepts such as trust, risk aversion, social norms, and the limits of rationality in decision-making. It highlights the importance of trust and expectations in influencing cooperative behavior. A lack of trust can lead to early defection, even when cooperation would be mutually beneficial.

Business Negotiation Example

Consider a negotiation between two companies (Company A and Company B) over a joint venture. Company A proposes a series of increasingly beneficial terms. Each company has the option to accept the offer (cooperate) or reject it and walk away (defect). If both cooperate until the end, they create a highly successful venture. If one defects early, they secure a smaller, but still significant, benefit, while the other company gains little or nothing.

The classic centipede game, with its frantic dodging and strategic mushroom placement, is a true arcade legend. Want to experience that same frantic fun digitally? Check out this awesome centipede video game adaptation – it really captures the spirit of the original. After playing the video game version, you might appreciate the simple yet challenging nature of the original centipede game even more.

The outcome depends on each company’s assessment of the other’s trustworthiness and their own risk aversion.

The Centipede Game and Game Theory Concepts

The Centipede Game provides valuable insights into several key game theory concepts.

Key Game Theory Concepts

The Centipede Game illustrates the Nash equilibrium (where no player can improve their outcome by unilaterally changing their strategy) and the subgame perfect equilibrium (a refinement of the Nash equilibrium that considers the optimal strategy in every possible subgame). It demonstrates that the Nash equilibrium doesn’t always predict real-world behavior.

The Centipede Game is a classic example of game theory, highlighting the tension between cooperation and self-interest. Think of it like this: each player’s decision is kind of like choosing the right “strap” for the job, in terms of risk versus reward – understanding the strap meaning in this context helps visualize the potential outcomes. Ultimately, in the Centipede Game, the choices you make determine whether you end up with a big win or a small one, or even nothing at all.

Challenges to Traditional Game Theory Assumptions

The Centipede Game challenges the assumption that players are perfectly rational and only concerned with maximizing their own payoff. The frequent observation of cooperation suggests that other factors, such as altruism and social norms, also influence decisions.

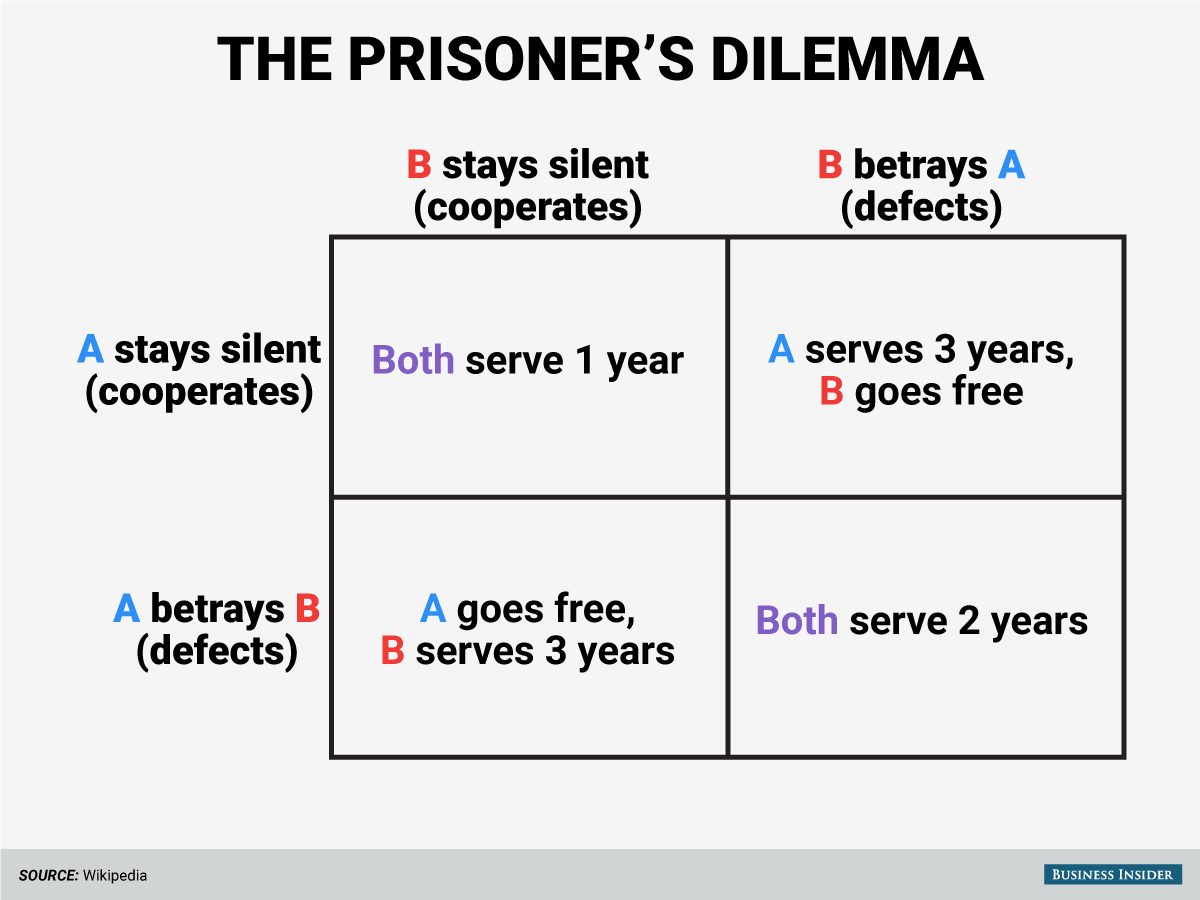

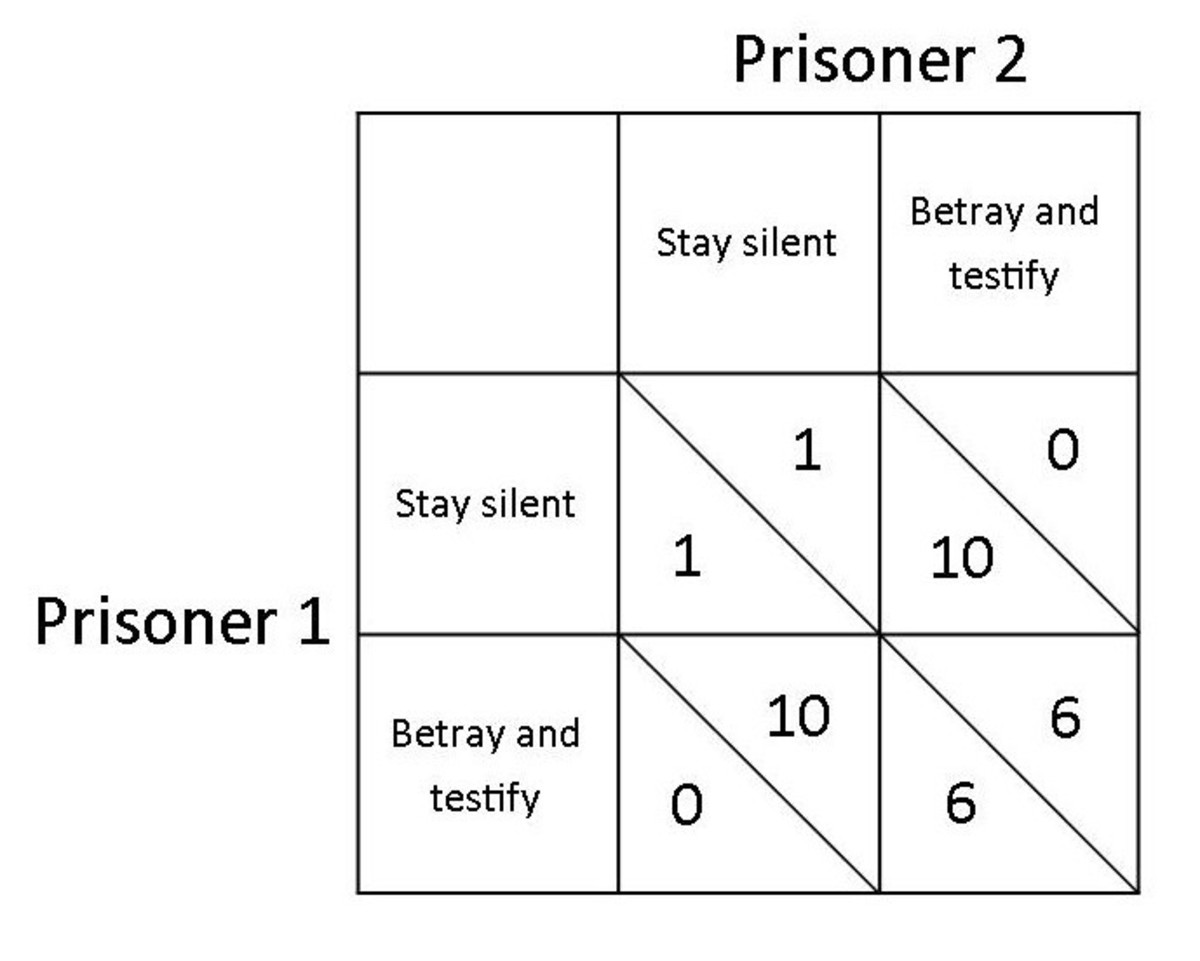

Comparison with the Prisoner’s Dilemma

Both the Centipede Game and the Prisoner’s Dilemma highlight the conflict between individual rationality and collective well-being. However, the Centipede Game has a sequential structure, while the Prisoner’s Dilemma is simultaneous. The Centipede Game allows for repeated interaction and the potential for building trust, whereas the Prisoner’s Dilemma is a one-shot interaction.

Comparison Table: Centipede Game vs. Prisoner’s Dilemma

| Feature | Centipede Game | Prisoner’s Dilemma |

|---|---|---|

| Structure | Sequential | Simultaneous |

| Interaction | Repeated | One-shot |

| Trust | Plays a significant role | Less relevant |

| Cooperation | Possible but not guaranteed | Rarely observed |

| Outcome | Often deviates from rational prediction | Predictable based on rationality |

Conclusive Thoughts

The Centipede Game, despite its apparent simplicity, offers a rich tapestry of strategic complexities and behavioral puzzles. Its paradoxical outcomes challenge traditional game theory assumptions and highlight the importance of considering psychological factors in predicting human behavior. By examining real-world experiments and theoretical variations, we gain valuable insights into cooperation, trust, and the interplay between rational self-interest and social norms.

Ultimately, the Centipede Game serves as a powerful tool for understanding the nuances of human decision-making in strategic interactions.

FAQ Compilation

What is the Nash Equilibrium in the Centipede Game?

The Nash Equilibrium is for the first player to defect immediately. While other outcomes are possible, this is the only equilibrium that survives backward induction.

How does the Centipede Game differ from the Prisoner’s Dilemma?

While both involve cooperation and defection, the Centipede Game is iterative, allowing for repeated opportunities for cooperation before the game ends. The Prisoner’s Dilemma is a one-shot game.

Why do people cooperate in the Centipede Game despite backward induction suggesting otherwise?

Experimental evidence shows people often cooperate, defying backward induction. This is attributed to factors like trust, risk aversion, altruism, and a desire for fairness.

Can the Centipede Game be applied to real-world scenarios beyond those mentioned?

Yes! It can model various situations involving sequential decisions and the potential for mutual gain through cooperation, such as negotiations, arms control, and environmental policy.